As a statistics and machine learning major at Carnegie Mellon, I have taken many math classes ranging from linear algebra and 3D calculus to probability and number theory. However, one of the most powerful ideas I have learned at CMU requires nothing more than 5th grade math.

The Problem

Consider this problem. Eleven scientists have access to a nuclear bomb. They wish to lock the bomb in a vault so that the vault can only be opened if six of the scientists are present. How many locks are required?

Each combination of six scientists requires a unique padlock. It can be shown that the minimal solution requires 462 locks and 252 keys.These numbers are impractical and grow exponentially as the number of scientists increases.

Instead of physical padlocks the scientists can use a secret code to lock the vault. But how should the secret code be protected?

The most secure solution would keep the code in a single well guarded location: a human brain, a computer, or a safe. However, this scheme is unreliable: a single misfortune (an untimely death, malfunction, or sabotage) would permanently lock the vault.

Copying the code and stashing it in multiple locations adds redundancy, but increases the risk of a security breach. Many copies offer many opportunities for the secret code to be stolen by attackers.

At its core the problem is this: how can we provide the redundancy of multiple backups without increasing the risk of a security breach? Our first attempts at a solution have all had significant drawbacks:

- Giving each combination of scientists a padlock is too complex and doesn’t scale beyond a few stakeholders.

- A single secret code is vulnerable to misfortune. If the code is forgotten or destroyed, the bomb becomes unaccessible.

- Storing copies of the secret code increases the risk of a security breach.

Threshold Schemes

Security— from nuclear vaults to online encryption— requires accessing and transferring data without revealing the original secret. Threshold schemes help protect information by splitting pieces of a secret— like the code to a nuclear vault— between a group. Recovering the original secret requires k of the n group members to recombine their shares of the secret.

Threshold schemes have the following properties:

- K or more shares can always always be combined to recover the original secret.

- Knowledge of K-1 shares leaves the secret undetermined— all possible values are equally likely.

It turns out that polynomials are all we need to implement a threshold scheme.

Polynomials 101

Polynomials are just lines that can be represented as an equation. The degree of a polynomial is the largest exponent. For example, y=2x2+10x+4 is a polynomial of degree two.

| Example Polynomial |

|---|

|

| A third degree polynomial. Four points are required to reconstruct the line. |

In general, each term in a polynomial can be written as cxk where c is a constant, x is a variable, and k is the exponent.

The following polynomial properties are relevant for threshold schemes:

- Every polynomial line crosses the y-axis exactly once.

- Every x-value corresponds to exactly one point on a line.

- A polynomial of degree k can be reconstructed from k+1 points.

As a final example, consider the polynomial y= x+10. This equation represents a straight line that extends from negative infinity to positive infinity and crosses the y-axis at a height of ten. Since the largest exponent is one, we can recreate the polynomial from any two points along the line. The process of recreating a polynomial from a collection of points is called polynomial interpolation and is used as the foundation for shamir secret sharing.

Shamir Secret Sharing

In 1979, Adi Shamir proposed a threshold scheme for sharing secrets.

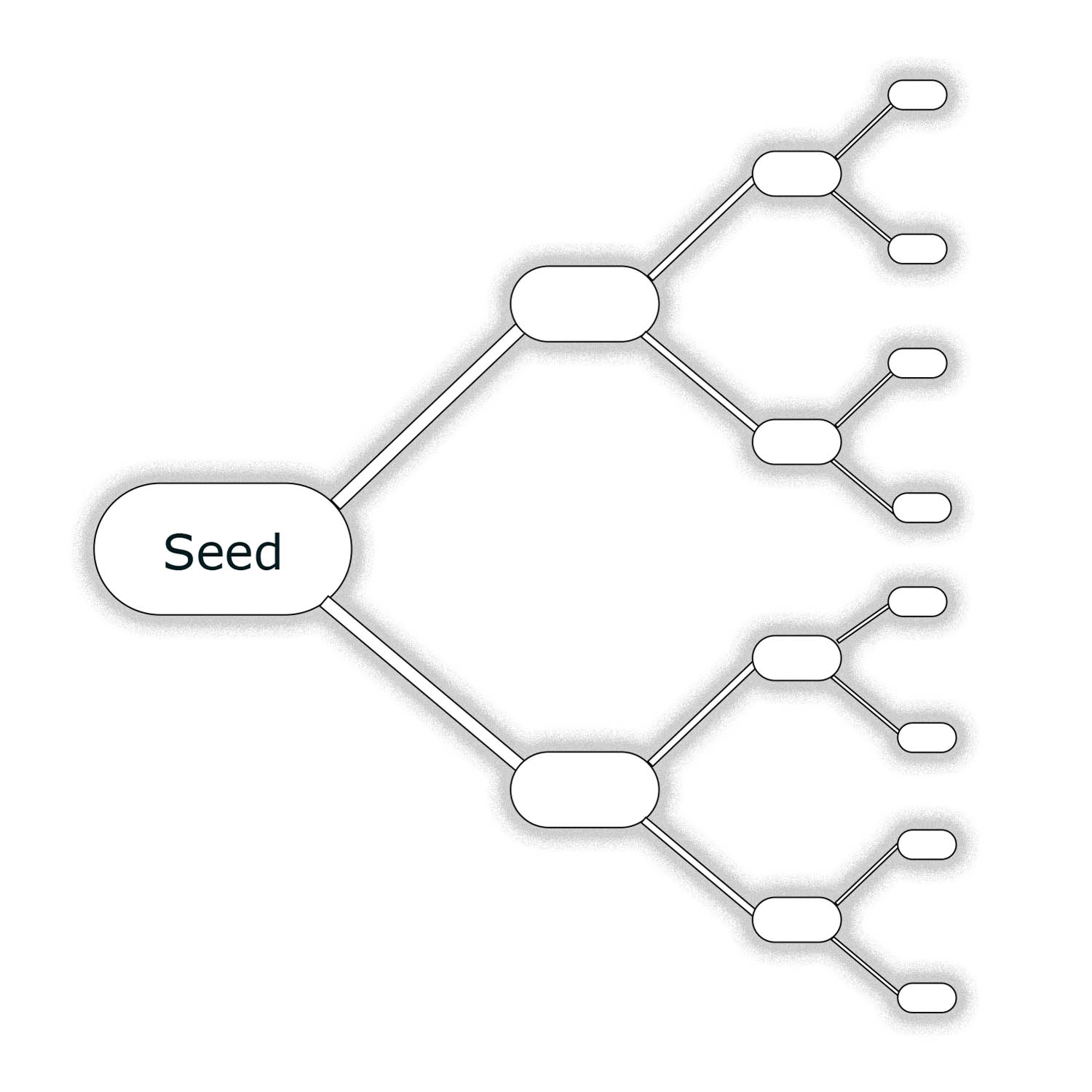

Shamir secret sharing divides data D into n shares, so at least k shares are required to reconstruct D.

At a very high level, shamir secret sharing hides data in a crowd— where the crowd is the infinite amount of numbers along the y-axis. The location of the secret data is given by a polynomial of degree k-1. The polynomial is broken into n shares and distributed among a group. K shares can be used to recover the secret’s location along the y-axis.

To create a k of n threshold scheme, shamir secret sharing uses the following steps.

Share Creation

- Convert data D into a number.

- Create an equation for an arbitrary polynomial of degree k-1.

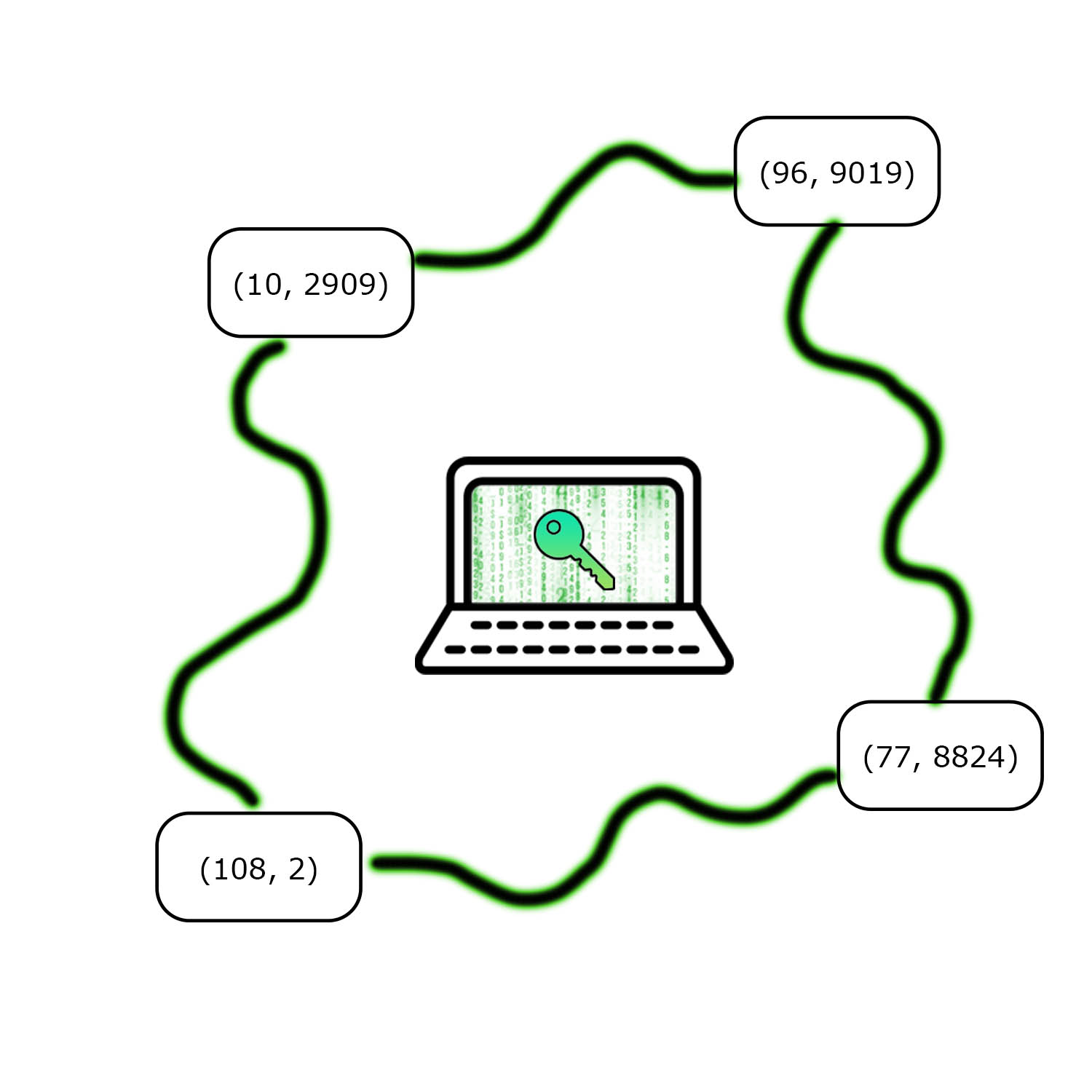

- Randomly select n points (xi, yi) from the polynomial.

- Distribute each share to members of the group.

Secret Recovery

- Collect at least k points from the group.

- Use lagrange interpolation to derive a k-1 polynomial.

- Convert the y-intercept of the polynomial back into the original secret.

Applications

Threshold schemes like shamir secret sharing are very useful when individuals with conflicting interests— like eleven scientists from different governments— must cooperate. In addition, shamir secret sharing gives the redundancy of copying a secret, while minimizing the risk of a security breach.

There are many uses of shamir secret sharing ranging from passwordless authentication to collaborative signatures. After learning about threshold schemes my sophomore year at CMU, I built a digital wallet that uses shamir secret sharing for authentication and account recovery. Over the past year, the wallet has received support from many foundations showing that sharing secrets online is a critical problem made easier by polynomials.

Keep Reading

Explore more ideas on the intersection of philosophy and performance.

SWORD

Digital wallets store sensitive secrets and billions of dollars. SWORD uses threshold cryptography to improve wallet security.

Digital Wallets

Every blockchain application requires a wallet that can send and sign transactions.

Asymmetric Cryptography

Public-private key pairs give everyone access to privacy and ownership.